Binary tree

In computer science, a binary tree is a tree data structure in which each node has at most two child nodes, usually distinguished as "left" and "right". Nodes with children are parent nodes, and child nodes may contain references to their parents. Outside the tree, there is often a reference to the "root" node (the ancestor of all nodes), if it exists. Any node in the data structure can be reached by starting at root node and repeatedly following references to either the left or right child.

Binary trees are used to implement binary search trees and binary heaps.

Contents |

Definitions for rooted trees

- A directed edge refers to the link from the parent to the child (the arrows in the picture of the tree).

- The root node of a tree is the node with no parents. There is at most one root node in a rooted tree.

- A leaf node has no children.

- The depth of a node n is the length of the path from the root to the node. The set of all nodes at a given depth is sometimes called a level of the tree. The root node is at depth zero.

- The height of a tree is the length of the path from the root to the deepest node in the tree. A (rooted) tree with only one node (the root) has a height of zero.

- Siblings are nodes that share the same parent node.

- A node p is an ancestor of a node q if it exists on the path from q to the root. The node q is then termed a descendant of p.

- The size of a node is the number of descendants it has including itself.

- In-degree of a node is the number of edges arriving at that node.

- Out-degree of a node is the number of edges leaving that node.

- The root is the only node in the tree with In-degree = 0.

Types of binary trees

- A rooted binary tree is a tree with a root node in which every node has at most two children.

- A full binary tree (sometimes proper binary tree or 2-tree or strictly binary tree) is a tree in which every node other than the leaves has two children. Sometimes a full tree is ambiguously defined as a perfect tree.

- A perfect binary tree is a full binary tree in which all leaves are at the same depth or same level, and in which every parent has two children.[1] (This is ambiguously also called a complete binary tree.)

- A complete binary tree is a binary tree in which every level, except possibly the last, is completely filled, and all nodes are as far left as possible.[2]

- An infinite complete binary tree is a tree with a countably infinite number of levels, in which every node has two children, so that there are 2d nodes at level d. The set of all nodes is countably infinite, but the set of all infinite paths from the root is uncountable: it has the cardinality of the continuum. These paths corresponding by an order preserving bijection to the points of the Cantor set, or (through the example of the Stern–Brocot tree) to the set of positive irrational numbers.

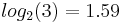

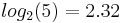

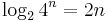

- A balanced binary tree is commonly defined as a binary tree in which the height of the two subtrees of every node never differ by more than 1,[3] although in general it is a binary tree where no leaf is much farther away from the root than any other leaf. (Different balancing schemes allow different definitions of "much farther"[4]). Binary trees that are balanced according to this definition have a predictable depth (how many nodes are traversed from the root to a leaf, root counting as node 0 and subsequent as 1, 2, ..., depth). This depth is equal to the integer part of

where

where  is the number of nodes on the balanced tree. Example 1: balanced tree with 1 node,

is the number of nodes on the balanced tree. Example 1: balanced tree with 1 node,  (depth = 0). Example 2: balanced tree with 3 nodes,

(depth = 0). Example 2: balanced tree with 3 nodes,  (depth=1). Example 3: balanced tree with 5 nodes,

(depth=1). Example 3: balanced tree with 5 nodes,  (depth of tree is 2 nodes).

(depth of tree is 2 nodes). - A rooted complete binary tree can be identified with a free magma.

- A degenerate tree is a tree where for each parent node, there is only one associated child node. This means that in a performance measurement, the tree will behave like a linked list data structure.

Note that this terminology often varies in the literature, especially with respect to the meaning "complete" and "full".

Properties of binary trees

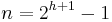

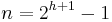

- The number of nodes

in a perfect binary tree can be found using this formula:

in a perfect binary tree can be found using this formula:  where

where  is the height of the tree.

is the height of the tree. - The number of nodes

in a complete binary tree is at least

in a complete binary tree is at least  and at most

and at most  where

where  is the height of the tree.

is the height of the tree. - The number of leaf nodes

in a perfect binary tree can be found using this formula:

in a perfect binary tree can be found using this formula:  where

where  is the height of the tree.

is the height of the tree. - The number of nodes

in a perfect binary tree can also be found using this formula:

in a perfect binary tree can also be found using this formula:  where

where  is the number of leaf nodes in the tree.

is the number of leaf nodes in the tree. - The number of null links (absent children of nodes) in a complete binary tree of n nodes is (n+1).

- The number of internal nodes in a Complete Binary Tree of n nodes is

.

. - For any non-empty binary tree with n0 leaf nodes and n2 nodes of degree 2, n0 = n2 + 1.[5]

-

- Proof:

- Let n = the total number of nodes

- B = number of branches

- n0, n1, n2 represent the number of nodes with no children, a single child, and two children respectively.

- Proof:

-

-

- B = n - 1 (since all nodes except the root node come from a single branch)

- B = n1 + 2*n2

- n = n1+ 2*n2 + 1

- n = n0 + n1 + n2

- n1+ 2*n2 + 1 = n0 + n1 + n2 ==> n0 = n2 + 1

-

Common operations

There are a variety of different operations that can be performed on binary trees. Some are mutator operations, while others simply return useful information about the tree.

Insertion

Nodes can be inserted into binary trees in between two other nodes or added after an external node. In binary trees, a node that is inserted is specified as to which child it is.

External nodes

Say that the external node being added on to is node A. To add a new node after node A, A assigns the new node as one of its children and the new node assigns node A as its parent.

Internal nodes

Insertion on internal nodes is slightly more complex than on external nodes. Say that the internal node is node A and that node B is the child of A. (If the insertion is to insert a right child, then B is the right child of A, and similarly with a left child insertion.) A assigns its child to the new node and the new node assigns its parent to A. Then the new node assigns its child to B and B assigns its parent as the new node.

Deletion

Deletion is the process whereby a node is removed from the tree. Only certain nodes in a binary tree can be removed unambiguously.[6]

Node with zero or one children

Say that the node to delete is node A. If a node has no children (external node), deletion is accomplished by setting the child of A's parent to null. If it has one child, set the parent of A's child to A's parent and set the child of A's parent to A's child.

Node with two children

In a binary tree, a node with two children cannot be deleted unambiguously.[6] However, in certain binary trees these nodes can be deleted, including binary search trees.

Iteration

Often, one wishes to visit each of the nodes in a tree and examine the value there, a process called iteration or enumeration. There are several common orders in which the nodes can be visited, and each has useful properties that are exploited in algorithms based on binary trees:

- Pre-Order: Root first, Left child, Right child

- Post-Order: Left Child, Right child, root

- In-Order: Left child, root, right child.

Pre-order, in-order, and post-order traversal

Pre-order, in-order, and post-order traversal visit each node in a tree by recursively visiting each node in the left and right subtrees of the root. If the root node is visited before its subtrees, this is pre-order; if after, post-order; if between, in-order. In-order traversal is useful in binary search trees, where this traversal visits the nodes in increasing order.

Depth-first order

In depth-first order, we always attempt to visit the node farthest from the root that we can, but with the caveat that it must be a child of a node we have already visited. Unlike a depth-first search on graphs, there is no need to remember all the nodes we have visited, because a tree cannot contain cycles. Pre-order is a special case of this. See depth-first search for more information.

Breadth-first order

Contrasting with depth-first order is breadth-first order, which always attempts to visit the node closest to the root that it has not already visited. See breadth-first search for more information. Also called a level-order traversal.

Type theory

In type theory, a binary tree with nodes of type A is defined inductively as TA = μα. 1 + A × α × α.

Definition in graph theory

For each binary tree data structure, there is equivalent rooted binary tree in graph theory.

Graph theorists use the following definition: A binary tree is a connected acyclic graph such that the degree of each vertex is no more than three. It can be shown that in any binary tree of two or more nodes, there are exactly two more nodes of degree one than there are of degree three, but there can be any number of nodes of degree two. A rooted binary tree is such a graph that has one of its vertices of degree no more than two singled out as the root.

With the root thus chosen, each vertex will have a uniquely defined parent, and up to two children; however, so far there is insufficient information to distinguish a left or right child. If we drop the connectedness requirement, allowing multiple connected components in the graph, we call such a structure a forest.

Another way of defining binary trees is a recursive definition on directed graphs. A binary tree is either:

- A single vertex.

- A graph formed by taking two binary trees, adding a vertex, and adding an edge directed from the new vertex to the root of each binary tree.

This also does not establish the order of children, but does fix a specific root node.

Combinatorics

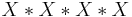

In combinatorics one considers the problem of counting the number of full binary trees of a given size. Here the trees have no values attached to their nodes (this would just multiply the number of possible trees by an easily determined factor), and trees are distinguished only by their structure; however the left and right child of any node are distinguished (if they are different trees, then interchanging them will produce a tree distinct from the original one). The size of the tree is taken to be the number n of internal nodes (those with two children); the other nodes are leaf nodes and there are n + 1 of them. The number of such binary trees of size n is equal to the number of ways of fully parenthesizing a string of n + 1 symbols (representing leaves) separated by n binary operators (representing internal nodes), so as to determine the argument subexpressions of each operator. For instance for n = 3 one has to parenthesize a string like  , which is possible in five ways:

, which is possible in five ways:

The correspondence to binary trees should be obvious, and the addition of redundant parentheses (around an already parenthesized expression or around the full expression) is disallowed (or at least not counted as producing a new possibility).

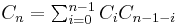

There is a unique binary tree of size 0 (consisting of a single leaf), and any other binary tree is characterized by the pair of its left and right children; if these have sizes i and j respectively, the full tree has size i + j + 1. Therefore the number  of binary trees of size n has the following recursive description

of binary trees of size n has the following recursive description  , and

, and  for any positive integer n. It follows that

for any positive integer n. It follows that  is the Catalan number of index n.

is the Catalan number of index n.

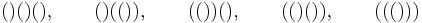

The above parenthesized strings should not be confused with the set of words of length 2n in the Dyck language, which consist only of parentheses in such a way that they are properly balanced. The number of such strings satisfies the same recursive description (each Dyck word of length 2n is determined by the Dyck subword enclosed by the initial '(' and its matching ')' together with the Dyck subword remaining after that closing parenthesis, whose lengths 2i and 2j satisfy i + j + 1 = n); this number is therefore also the Catalan number  . So there are also five Dyck words of length 10:

. So there are also five Dyck words of length 10:

.

.

These Dyck words do not correspond in an obvious way to binary trees. A bijective correspondence can nevertheless be defined as follows: enclose the Dyck word in a extra pair of parentheses, so that the result can be interpreted as a Lisp list expression (with the empty list () as only occurring atom); then the dotted-pair expression for that proper list is a fully parenthesized expression (with NIL as symbol and '.' as operator) describing the corresponding binary tree (which is in fact the internal representation of the proper list).

The ability to represent binary trees as strings of symbols and parentheses implies that binary trees can represent the elements of a free magma on a singleton set.

Methods for storing binary trees

Binary trees can be constructed from programming language primitives in several ways.

Nodes and references

In a language with records and references, binary trees are typically constructed by having a tree node structure which contains some data and references to its left child and its right child. Sometimes it also contains a reference to its unique parent. If a node has fewer than two children, some of the child pointers may be set to a special null value, or to a special sentinel node.

In languages with tagged unions such as ML, a tree node is often a tagged union of two types of nodes, one of which is a 3-tuple of data, left child, and right child, and the other of which is a "leaf" node, which contains no data and functions much like the null value in a language with pointers.

Arrays

Binary trees can also be stored in breadth-first order as an implicit data structure in arrays, and if the tree is a complete binary tree, this method wastes no space. In this compact arrangement, if a node has an index i, its children are found at indices  (for the left child) and

(for the left child) and  (for the right), while its parent (if any) is found at index

(for the right), while its parent (if any) is found at index  (assuming the root has index zero). This method benefits from more compact storage and better locality of reference, particularly during a preorder traversal. However, it is expensive to grow and wastes space proportional to 2h - n for a tree of height h with n nodes.

(assuming the root has index zero). This method benefits from more compact storage and better locality of reference, particularly during a preorder traversal. However, it is expensive to grow and wastes space proportional to 2h - n for a tree of height h with n nodes.

This method of storage is often used for binary heaps. No space is wasted because nodes are added in breadth-first order.

Encodings

Succinct encodings

A succinct data structure is one which takes the absolute minimum possible space, as established by information theoretical lower bounds. The number of different binary trees on  nodes is

nodes is  , the

, the  th Catalan number (assuming we view trees with identical structure as identical). For large

th Catalan number (assuming we view trees with identical structure as identical). For large  , this is about

, this is about  ; thus we need at least about

; thus we need at least about  bits to encode it. A succinct binary tree therefore would occupy only 2 bits per node.

bits to encode it. A succinct binary tree therefore would occupy only 2 bits per node.

One simple representation which meets this bound is to visit the nodes of the tree in preorder, outputting "1" for an internal node and "0" for a leaf. [1] If the tree contains data, we can simply simultaneously store it in a consecutive array in preorder. This function accomplishes this:

function EncodeSuccinct(node n, bitstring structure, array data) {

if n = nil then

append 0 to structure;

else

append 1 to structure;

append n.data to data;

EncodeSuccinct(n.left, structure, data);

EncodeSuccinct(n.right, structure, data);

}

The string structure has only  bits in the end, where

bits in the end, where  is the number of (internal) nodes; we don't even have to store its length. To show that no information is lost, we can convert the output back to the original tree like this:

is the number of (internal) nodes; we don't even have to store its length. To show that no information is lost, we can convert the output back to the original tree like this:

function DecodeSuccinct(bitstring structure, array data) {

remove first bit of structure and put it in b

if b = 1 then

create a new node n

remove first element of data and put it in n.data

n.left = DecodeSuccinct(structure, data)

n.right = DecodeSuccinct(structure, data)

return n

else

return nil

}

More sophisticated succinct representations allow not only compact storage of trees but even useful operations on those trees directly while they're still in their succinct form.

Encoding general trees as binary trees

There is a one-to-one mapping between general ordered trees and binary trees, which in particular is used by Lisp to represent general ordered trees as binary trees. To convert a general ordered tree to binary tree, we only need to represent the general tree in left child-sibling way. The result of this representation will be automatically binary tree, if viewed from a different perspective. Each node N in the ordered tree corresponds to a node N' in the binary tree; the left child of N' is the node corresponding to the first child of N, and the right child of N' is the node corresponding to N 's next sibling --- that is, the next node in order among the children of the parent of N. This binary tree representation of a general order tree is sometimes also referred to as a left child-right sibling binary tree (LCRS tree), or a doubly chained tree, or a Filial-Heir chain.

One way of thinking about this is that each node's children are in a linked list, chained together with their right fields, and the node only has a pointer to the beginning or head of this list, through its left field.

For example, in the tree on the left, A has the 6 children {B,C,D,E,F,G}. It can be converted into the binary tree on the right.

The binary tree can be thought of as the original tree tilted sideways, with the black left edges representing first child and the blue right edges representing next sibling. The leaves of the tree on the left would be written in Lisp as:

- (((N O) I J) C D ((P) (Q)) F (M))

which would be implemented in memory as the binary tree on the right, without any letters on those nodes that have a left child.

See also

- 2-3 tree

- 2-3-4 tree

- AA tree

- B-tree

- Binary space partitioning

- Elastic binary tree

- Huffman tree

- Kraft's inequality

- Random binary tree

- Recursion (computer science)

- Red-black tree

- Rope (computer science)

- Self-balancing binary search tree

- Strahler number

- Threaded binary

- Tree of primitive Pythagorean triples#Alternative methods of generating the tree

- Unrooted binary tree

Notes

- ^ "perfect binary tree". NIST. http://www.nist.gov/dads/HTML/perfectBinaryTree.html.

- ^ "complete binary tree". NIST. http://www.nist.gov/dads/HTML/completeBinaryTree.html.

- ^ Aaron M. Tenenbaum, et. al Data Structures Using C, Prentice Hall, 1990 ISBN 0-13-199746-7

- ^ Paul E. Black (ed.), entry for data structure in Dictionary of Algorithms and Data Structures. U.S. National Institute of Standards and Technology. 15 December 2004. Online version Accessed 2010-12-19.

- ^ Mehta, Dinesh; Sartaj Sahni (2004). Handbook of Data Structures and Applications. Chapman and Hall. ISBN 1584884355.

- ^ a b Dung X. Nguyen (2003). "Binary Tree Structure". rice.edu. http://www.clear.rice.edu/comp212/03-spring/lectures/22/. Retrieved December 28, 2010.

References

- Donald Knuth. The art of computer programming vol 1. Fundamental Algorithms, Third Edition. Addison-Wesley, 1997. ISBN 0-201-89683-4. Section 2.3, especially subsections 2.3.1–2.3.2 (pp. 318–348).

- Kenneth A Berman, Jerome L Paul. Algorithms: Parallel, Sequential and Distributed. Course Technology, 2005. ISBN 0-534-42057-5. Chapter 4. (pp. 113–166).

External links

- flash actionscript 3 opensource implementation of binary tree — opensource library

- [2] — GameDev.net's article about binary trees

- [3] — Binary Tree Proof by Induction

- Balanced binary search tree on array How to create bottom-up an Ahnentafel list, or a balanced binary search tree on array

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||